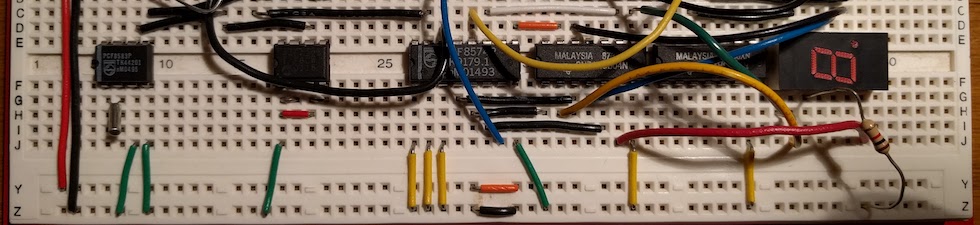

Lately I’ve been decluttering, and I went through some old boxes of electronics components. This hobby was a significant part of my childhood. Some kids collected pokemon cards, other kids watched cartoons… I tinkered with electronics.

The decluttering project is partially a desire to reduce the space the items take up in storage and partly a trip down memory lane. There were many positive aspects to this hobby. I created a science fair project, I entertained myself during the cold Minnesota winters, and I practiced some of the same troubleshooting and analytical skills that I use today in my job as a software engineer.

At the time, my dad was a physics professor and had a shelf full of electronics books, so it was also a way to connect with Dad. I kept an engineering notebook and right now I have in front of me a page about RC circuits in Dad’s handwriting. 2 pages later I have a circuit diagram I made of how a 12-key keypad button could be wired. I wanted to know how everything worked, and I collected magazine articles and made meticulous component lists complete with prices from the DigiKey catalog.

One interesting notebook entry is from 2010 in which I was a little more reflective and wrote:

I find that I am very covetous of other people’s projects. I have a lot of stuff to hack — a whole closetful — but I don’t use it very often. … I like hacking projects that are useful. I don’t really like the art ones.

Reading this I can tell I had a very strong pragmatic bent even back in 2010. I still have this bent today, but lately I am finding that it stifles creativity to always be trying to find a practical use for everything. At the same time, I also realize I have a “whole closetful” of ideas and limited time so I have to prioritize which things to work on. It also seems helpful to bring projects to a point where they can be shared or published about. In doing so, you are forced to distill and express what you learned.

It is a challenge for me to deal with the collection of components due to the memories attached to them. I sold a couple items on eBay, and I suppose the thing to do is to take the remaining components and either auction them as a lot or donate them to a maker space.